The Introspectiveness of Neural Networks

Neural networks are wonderful things, to say the least. They are undoubtedly the state-of-the-art techniques for many applications (if not all) ranging from language translations all the way to self-driving cars. Modern day neural networks, combined with other machine learning concepts such as reinforcement learning, have been able to crush the best human Go players in the world. Go is a game that has more possible board configurations (10^170 to be exact) than the number of atoms in the universe! In fact, just a little over two weeks ago, the Elon Musk-backed research lab OpenAI revealed an AI bot in the popular game of Dota 2 that just manhandled professional e-sport players in 1-vs-1 matches.

A web-based tool that the Data Visualization team uses over at Uber to explore self-driving car research data

A web-based tool that the Data Visualization team uses over at Uber to explore self-driving car research data

OpenAI’s video showcasing all the different tactics/behaviors that its bot learned on its own. Mind you, there were no hundreds of if statements to program these behaviors like one would usually do in a traditional programming setting. The bot just played a lifetime’s worth 1-vs-1 matches against itself with minimal supervision from the researchers. And it just learns.

To be honest, I can dedicate this entire post to the remarkable accomplishments of neural networks. But now, I want to talk about neural networks from a different perspective, mainly it’s origin story: how it came to be and why it’s our best shot at truly intelligent machines and why it has more far-reaching consequences than we might have imagined.

Let’s go back to what originally inspired neural networks in the first place, our brains. We are all born with these insanely powerful and versatile computers in our heads that allow us to learn truly anything. We immediately learn to see and hear without any effort, and we can pretty complex math and physics, and finally, we can learn to create some of the most impressive engineering feats all the way from smartphones to reusable rockets.

So the brain can do all these different and amazing things. The million dollar question is, how? A reasonable guess would be that the brain works like a computer with a thousand different programs to do a thousand different things. A crude example would be that if I learnt how to speak French, the brain would generate some sort of French speaking module and just piece it in with the thousand different other modules that I already knew how to do.

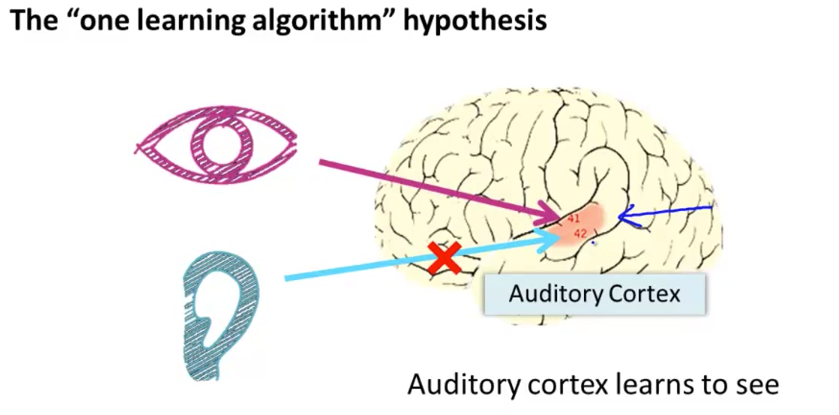

On the other hand, what if the exact opposite is true? Instead, the brain only knows one learning algorithm that is capable of learning, well, anything. Although this is still a hypothesis, it is one that has some really mind-blowing evidences. Let me share with you my favorite:

In a 1992 neuroscience paper by Roe et al., they rewired a ferret’s retinal input into the auditory cortex [1]. Your auditory cortex is responsible for processing the sound signals you hear, allowing you to understand basic words and speech. The result of this neural-rewiring is nothing short of jaw-dropping: the auditory cortex learned how to process visual information coming from the ferret’s eyes, and in every sense, learned how to see.

A neural-rewiring of the brain. This is the biological equivalent of plugging your webcam input into your sound card of your computer. [2]

A neural-rewiring of the brain. This is the biological equivalent of plugging your webcam input into your sound card of your computer. [2]

In another earlier neural-rewiring experiment by Metin and Frost in 1989, they rewired the same retinal input of hamsters (instead of ferrets) into the somatosensory cortex, which is responsible for your sense of touch [3]. As you might have guessed, these hamsters learned how to see without any issues. Overall, if the same section of the physical brain tissue can learn how to see, hear, and touch, surely, there must be a general learning algorithm that can do all these things, and more. At least, it seems very unlikely that the brain has three different learning algorithms for your sight, sound, and touch.

This brings me to the ultimate quest of AI and truly intelligent machines. If we can figure out and understand the brain’s learning algorithm and develop some close approximation to it for a computer, then this might be the best shot we have towards Artificial General Intelligence, one that can help us someday solve humanity’s problems in ways such as preventing global warming or outbreaks of diseases.

It’s hard not to get carried away here because even the slightest progress towards such general intelligence can tremendously benefit our world. (As a positive person, I assume here that AI will be used mainly for the good of mankind. I understand that this might not be the case but that topic is best saved for another blog post). However, the sad truth is that we are nowhere near achieving the ultimate dream of general intelligence, even with the ground-breaking research in neural networks today. This is mainly because, we still are nowhere near understanding the full complexities of how our brain learns, other than the fact that there’s this general learning algorithm. In fact, do a google search right now for “how does the brain work”. The results can go into very good detail about the structure and components of the brain but there’s definitely something left to be desired in how it all comes together. Just take a look at this short summary from the U.S. National Library of Medicine - PubMed Health Journal [4]:

The brain works like a big computer. It processes information that it receives from the senses and body, and sends messages back to the body. But the brain can do much more than a machine can: humans think and experience emotions with their brain, and it is the root of human intelligence.

It certainly is the root of human intelligence, which is why I am so insistent that unlocking the secrets of the brain can allow us to design better neural networks. I’ll give you another favorite example to prove this.

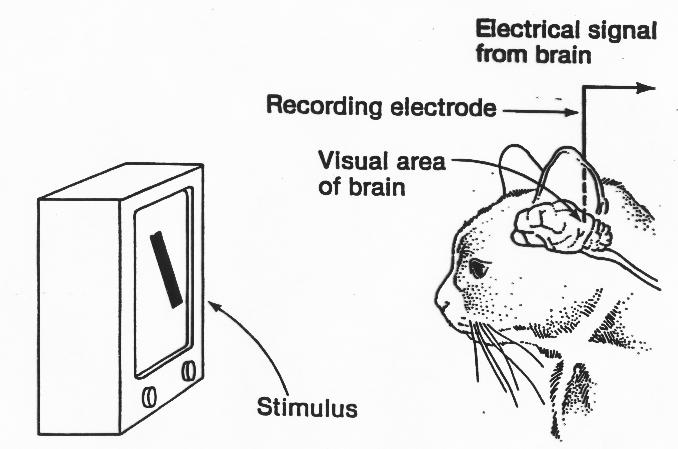

In 1959, Hubel and Wiesel were studying the visual cortex of a cat, by observing the early visual area of the cat brain, as the cat was looking at specific patterns on the screen [5].

High-level setup of the Hubel and Wiesel’s experiment.

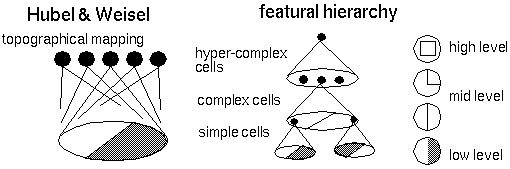

They realized that a neuron/cell would only turn on for edges in a particular orientation and that orientation only. Through this, they devised a model of how the visual cortex processes information. They found that nearby cells in the cortex represented and processed nearby regions in the visual field, preserving the spatial information of whatever the cat was seeing. Further, they found that were was an entire hierarchy of rows of cells. The most low level cells were named simple cells as they only reacted to a particular orientation of an edge. Through all these experiments, Hubel and Wiesel hypothesized that the visual cortex can be described by a hierarchical organization of simple cells that fed into complex cells which have more complicated activations and can form higher level representations. These simple cells would have translationally invariant and locally receptive fields.

Feature hierarchy of cells that processes visual information.

(At this point, if you are aware of how Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) work, you should already see the uncanny resemblance) Hubel and Wiesel eventually won a nobel prize for their amazing discoveries, and it inspired the computer vision community to reproduce this result. In the 1980s, Fukushima came up with the Neocognitron, which was basically a multilayered neural network for pattern recognition tasks. Eventually, Yann LeCun et al. built the first backpropogatable CNN, famously dubbed LeNet, in 1998. Fast-forwarding to today, CNNs not only dominate the computer vision world in terms of raw benchmark performance whether it’s MNIST or ImageNet, but is also deployed in tasks such as language translation (check out https://www.deepl.com/translator - they use a CNN over the more traditional RNN, and supposedly get better results).

The previous example was quite dense so let me summarize: the understanding of how the visual cortex works (not simply where it is inside the brain) allowed us to essentially come up with CNNs, a far more versatile version of a neural network for computer vision.

So far we’ve taken a look at the origin story of neural networks. The single learning algorithm hypothesis and its mind-blowing evidence motivates neural networks as not only a powerful learning algorithm, but perhaps the algorithm that general intelligence can be built upon. Plus, we examined a Nobel-prize worthy discovery into how the visual cortex processes images inside the brain. More importantly, we saw how this inspired the CNN that dominates today’s world of computer vision.

These two things constantly remind me of the introspectiveness of neural networks: their advancement relies on not only progress in machine learning, but also progress in neuroscience. The latter is undoubtedly the harder one to achieve, but also the more likely to fundamentally impact deep learning, and therefore should never be lapsed, especially in the minds of individuals interested in deep learning research and careers.

< References >

[1] Roe, A. W., Pallas, S. L., Kwon, Y. H. & Sur, M. Visual projections routed to the auditory pathway in ferrets: receptive felds of visual neurons in the primary auditory cortex. J. Neurosci. 12, 3651±3664 (1992).

[2] A. Ng, Lecture 4.2-Neurons and the brain: The “one learning algorithm” hypothesis., (2012)

[3] Metin, C. & Frost, D. Visual responses of neurons in somatosensory cortex of hamsters with experimentally induced retinal projections to somatosensory thalamus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 86, 357–361 (1989).

[4] “How Does the Brain Work?” National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 29 Dec. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0072486/.

[5] Hubel, D. H. & Wiesel, T. N. (1959). Receptive fields of single neurons in the cat’s striate cortex. J. Physiol. 148, 574-591.